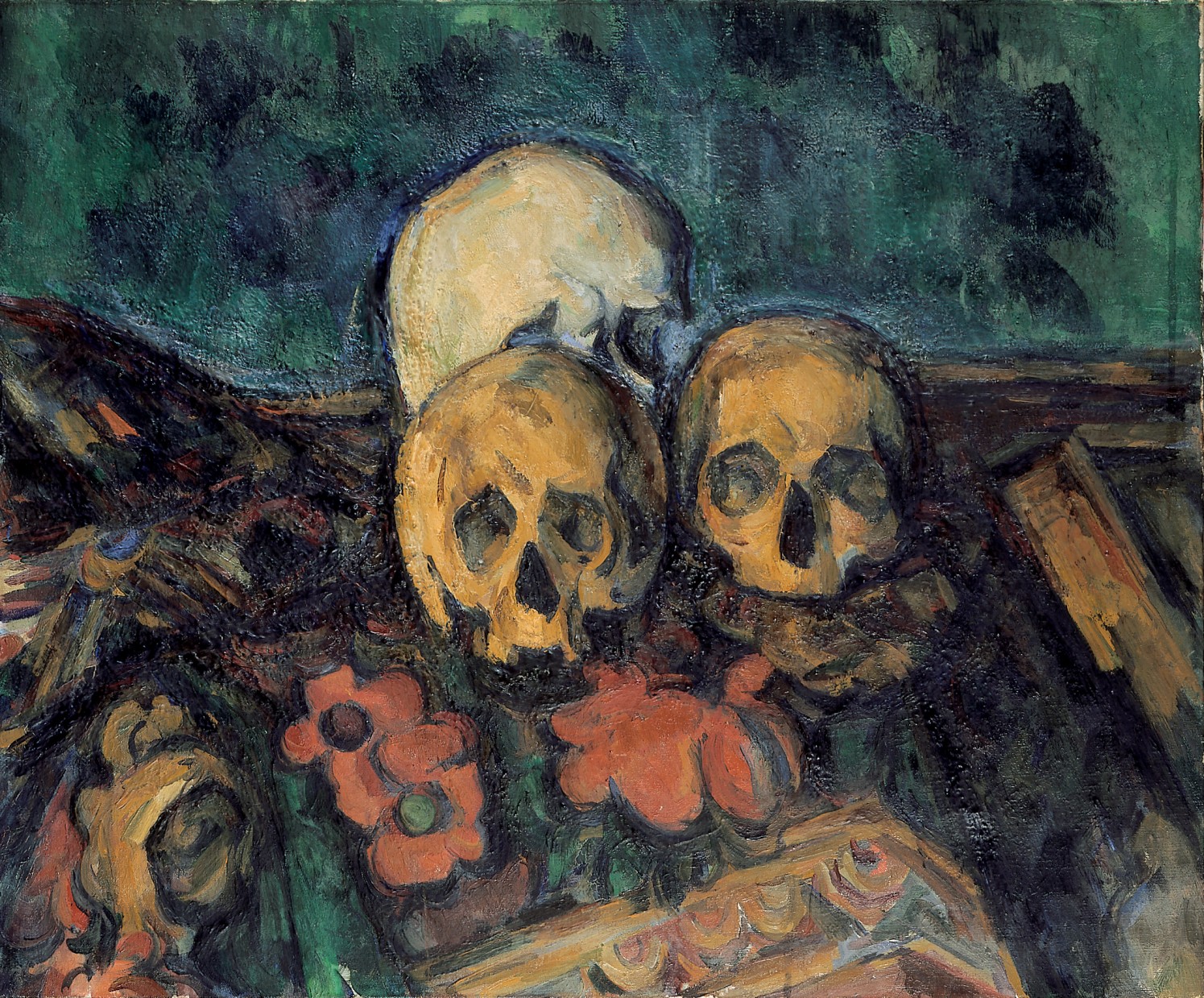

The last painting you see as you leave Tate Modern’s Cézanne retrospective is Three Skulls on a Patterned Carpet (1904). Done two years before the artist’s death, it is dark and oppressive, literal in its preoccupations.

The three skulls speak of death and interiority, of subjective meditation on the limits of human life. The carpet which rises all around them, High Victorian with its illusionistic red flowers and brownish folds, is fecundity embodied: all blooming and dying. The painting thematizes a split, ever-present in Cézanne, between lived time – the time, equally, of the painter making the painting and of the human beings whose skulls these once were – and the longer durée of material time, the time of solid objects and raw matter, during which our own skeletons will endure when we do not. The flesh that covers them will recede; the force and intelligence that moves them will vanish; but our bones will live on at a different rhythm, under different forms of propulsion, becoming, perhaps, props on an artist’s table. Skulls, in other words, are like paintings: they outlast their original owners (it is marvellous to see the thick, bubbled paint that still stands off the contours of the left two skulls, a hundred years and more after they were painted).

These are morbid thoughts. They make sense coming at the end of a retrospective. But they risk overdetermining our understanding of the artist. Cézanne worked on other subjects than skulls in his last years – the three great Large Bathers for instance, of which only one, belonging to the National Gallery, is on show at the Tate. Or the views of Mont Sainte-Victoire done from his studio roof. Or the mighty portraits of Vallier his gardener. Death was not his sole concern. Nor did death, when it appeared, necessarily call for such seriousness. It could be funny; one need only look at Chateau Noir (1900-4), hung near to Three Skulls, to see this. The painting’s gothic flourishes are absurd. Lancet windows bulge like eyeballs, bare tree branches form skeleton fingers. It is as unsparing a send-up of the tendency to allegorize mortality as Northanger Abbey. We should not look to the Three Skulls, then, for some neat, closed statement on mortality. Certainly, the painting is a memento mori, done in the tradition of Cézanne’s heroes Titian and Poussin. But we should ask what the difference is between such a painting, done by an ageing Cézanne as the twentieth century dawned, and those of the painters on whom he drew. What was death’s social content at this point in the history of modernism? What marked it off from Et in Arcadia Ego?

Answering such questions requires knowledge of where Cézanne was coming from, of the artistic traditions on which he drew, and of the society in which he lived: the norms and expectations of the modernizing French bourgeoisie that come under such pressure in his paintings. Such considerations are well served by the hanging arrangements in the Tate show. With the exception of the last room, which treats the late Cézanne, the exhibition is organized either thematically or pedagogically, not chronologically. There is a room for the views of L’Estaque; one for the artist’s beloved Mont Sainte-Victoire; one for the bathers; one for the still lives; and another for portraits of the artist’s wife and young son. We go on encountering early paintings, from the 1860s or early 1870s, throughout. Sometimes, these encounters prompt re-evaluation.

Room 2 hangs some of the great landscapes, typically read in terms of close empirical observation, across from a few of the more fanciful products of Cézanne’s sexual imagination. What does it do to The Francois Zola Dam (1878-9), whose swirling precipitous landscape the formalist art historian Roger Fry found so perfect, to come upon it opposite the seldom seen 1876-7 version of L’Après-midi á Naples, and realize these works were almost contemporaneous? Or to turn from MoMA’s peerless Still Life with Fruit Dish (1879-80) and find The Battle of Love (1880)? Fry thought paintings like L’Après-midi and The Battle spoke to a weaker strain in Cézanne’s painting, ‘the baroque contortions and involutions with which his inner visions presented themselves to his mind’. ‘Baroque contortions’ is not a bad term for what is going on in L’Après-midi. Its central two figures embrace so closely that their bodies almost fuse. Look where the left-hand woman’s left leg and back meet the right leg of her androgynous companion, how they seem to issue from a single body united by her loose black plait. Attraction and revulsion are mingled here, and attached to the naked human form, in a manner that is further allegorized by the wrestling (or coupling?) figures in The Battle of Love.

Fry could never muster much affection for such ambiguities. He preferred the ‘ordered architectural design’ achieved in Cézanne’s images of the external world: landscape and still life in particular. It is a nice touch to see Fry’s notebooks displayed next to Still Life with Fruit Dish. His diligent, rectilinear sketches and excited handwriting convey the breathlessness of his attempts to comprehend the sheer novelty of what he was seeing. The words he found – words for Cézanne’s muteness and impenetrability; his bizarre conservative politics; the ‘tragic, menacing, noble or lyrical’ sides of his art; its repeated efforts at ‘synthesis’ – these go on resonating. But the gap between the sketches on the page and the canvas on the wall is glaring. Fry’s drawings are neat and ordered. They reflect his conviction that logic and synthesis were the paintings’ ultimate results. Cézanne’s painting, on the other hand, fairly pulses with sickly illumination. The blue wallpaper flowers take on a life of their own. I can never escape the impression that the back wall is no wall at all, but sky. Blue seeps around the objects. It makes the yellow and red highlights on the apples blaze brighter.

Moving from the sexual fantasies of paintings like L’Après-midi and The Battle of Love to Cézanne’s more innocuous subjects helps us discern the mingled presence of desire, uncertainty, and fear in both. Take the two paintings of The Bay of Marseille Seen from L’Estaque that hang side-by-side in Room 5. The first was done in 1878-9 and usually hangs in the Musée d’Orsay, the other is most likely from 1885 and comes from the Art Institute of Chicago. Both meditate on the painter’s desire to fix the view before him into comprehensible form, to have it add up, and the failures and frustrations implicit in the attempt. The splendid ridge of deep, scrubby green that descends from left to right in the Orsay painting encapsulates this feeling. It is broken at its centre by the odd pairing of a tiny, dun coloured house and a tree with an ochre canopy. The house is bright and inhuman, with the merest ghost of a window. The tree is bizarre, thrusting up from all that green, haloed in blue and white. Is it dead? Killed by some blight that will carry off its dry leaves? Is it no tree at all, but a puff of smoke from the chimneystack directly below? Or a tree viewed through smoke? The foreground piles up questions and uncertainties. They are the fruits of sustained looking. In the Chicago picture, smoke streams from another chimney, its blue-grey scrawl a synecdoche for the power and deficiencies of the painter’s brush. Form is fixed, only to endlessly unravel.

The question posed in such passages is this: what if an image of the world won at the greatest cost, at the greatest proximity, returns as something ungraspable? What if knowledge, at close range, adds up to confusion? The view across the bay of Marseille, at the opposite shore, speaks to this fear. In both paintings, distance has ironed out the peculiarities of the foreground, but at the cost of all lived particularity. It is as if in order to understand the scene, the painter had to kill it. The shadows that wreak havoc in the foreground of the Chicago painting have been pushed right off the hills on the other side of the bay. They balance on top of them like rakish hats. The diagonal ridge, tinged green, that runs down to the bay’s far shore on the right of the Orsay painting, reads like an answer to the broken diagonal in the foreground with its smoking tree. Nothing living breaks its surface. Its rationality is chilling.

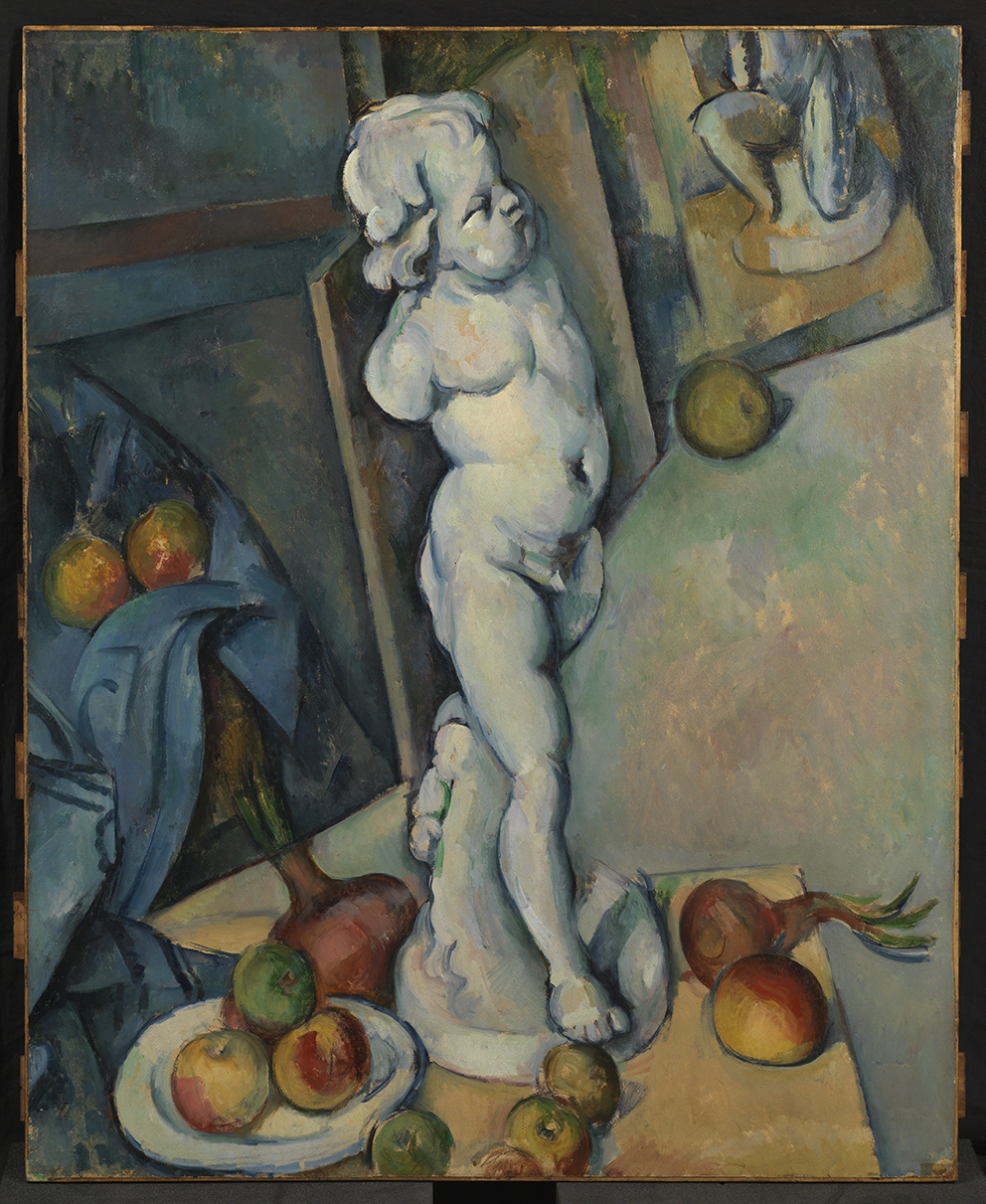

The paintings at L’Estaque are typical of Cézanne’s mature landscapes. We can never get a grip on them. The space they offer for imaginative participation is always either too close or too far away. Something similar happens in the still lives, of which the show contains an astounding selection. A single wall in room 7 is worth the price of entry alone: it holds the two versions of Still Life with Plaster Cupid, from the Courtauld in London and the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, as well as Still Life with a Ginger Jar and Eggplants (1893-4) from the Met and the Getty Museum’s Still Life with Apples (1893-4). All were done between 1893 and 1895, at Jas de Bouffan, the family estate where Cézanne moved after the death of his father. The sheer range of effects achieved across contemporaneous paintings with similar, often identical subject matter, is remarkable. Just look at the shift in atmosphere between the Met’s Still Life and the Getty’s, how two paintings in which blue is the dominant note – the blue of the walls, of the air, of the fabric à l’indienne, of the stalwart ginger jar – make such different material out of the same colour. The former is icy; the latter suffused with a green that seems to emanate from the melon’s bowling-ball surface. Look at the different kinds of disorientation achieved in the two Cupids. Space, in the Courtauld painting, is tipped and tilted. The cupid rocked on its table, the canvases stacked against the walls and the bucking floor that rises up almost parallel with the picture plane describe a mad architecture. The Stockholm version came later. It resolves its predecessor’s space into a comprehensible linear construction; I imagine even Cézanne pulling back from the full implications of his earlier Cupid. Now, at least, we are level with the tabletop. The studio-floor, so productive of spatial confusion (why is ground-level in Cézanne never a source of certainty?), is out of sight. But in its absence, the objects on the table are transformed. The cupid’s mutilation reads more clearly from this angle. Whole patches of canvas poke through its plaster face. Spilling across the table, its folds twisted up into a clam’s mouth, the blue fabric acquires an eerie vitality.

There was a time when the effects of such paintings – the way they have of at once framing a scene, with dazzling immediacy, and rendering it alien, incomprehensible – were read in terms of autonomy. Like Cézanne himself, leaving behind theatrical subject matter and Paris salons for the peasants and produce of Aix, these paintings withdraw. They are dense, negative, particular. This negativity seemed to answer the question of their modernity: how it was that this most innovative of painters, a beacon to generations of subsequent modernists, could have assembled his greatest achievements from such defiantly pre-modern subject matter. Turning from modernity in revulsion, seeking more and more extreme models of refusal, the paintings registered modernity’s effects with unprecedented sensitivity. This has been one answer to the biographical problem of Cézanne’s later political sympathies: his mistrust for revolutionary politics, his anti-Dreyfusism, his increasingly conservative Catholicism. None of it mattered if the art itself registered a different set of aesthetic and political commitments. Fry put it this way:

At bottom this strange man, who seemed in life to be of an exasperating innocence, this man who read nothing but the Catholic daily paper, trusted always to the Pope for direction, and believed all the reassuring plausibilities of the social and intellectual reaction, had none the less a great intellect where his one passion was concerned, in whatever affected his art.

The contemporary art world no longer has much tolerance for this kind of argument. We do not insulate art from the world around it. We want our artists to share our politics. Their lives should be exemplary. The Tate show makes no mention of Cézanne’s later opinions. Instead, in room 3, titled ‘Radical Times’, the curators attempt to unsettle the image of an isolated reactionary pursuing his art in denial of wider society. They make the case for a man whose paintings, at least in his youth, responded to progressive causes. Scipio (1866-8) depicts a half-clothed black man, a model of the same name at the Academie Suisse about whom little else is known. Cézanne has shown him seated, eyes shut, resting on a white sheet with arms thrown forward. It is a beautiful painting, muscled like a mannerist nude, a figure study in exhaustion that draws, clearly, on prototypes developed in the imagery of abolitionism. The American Civil War had barely ended; slavery in the French dominions was a none-too-distant memory. It is fascinating to see Cézanne responding sympathetically to this discourse. But one needs to ask why this interest in racial justice, briefly gained, was so quickly lost. Why do the great paintings of the following decades shed the signs of human struggle? What was the character of this loss, this withdrawal, accompanied as it was by an art of unprecedented aesthetic boldness? Was it flight from the modern world – from its horrors and its challenges – or a confrontation with some of its deepest implications?

At stake here is the character of Cézanne’s withdrawal. What was lost and what was achieved? One answer to this is given by the treatment of death in Three Skulls, and two paintings that hang near to it at the end of the Tate show – Still Life with Apples and Peaches (c.1905) and Still Life with Ginger Jar, Sugar Bowl and Oranges (1902-6). In each, the blue that suffused a whole moment of Cézanne’s still lives has been all but extinguished. The shutters are closed, the outside world banished. Touches of blue remain – on the creases of a cloth or the highlights of a piece of fruit – but the overwhelming tones are the browns of the wall and the reds of the patterned carpet. The sense of loss is overpowering. The world collapses to the dimensions of an interior. Fruit has turned rust-coloured. Death appears in these paintings as a withdrawal into the private sphere, a shuttering-up of the artist in his grand house, with his beloved objects. In the process, the whole tragedy of modern capitalism which is Cézanne’s great theme – the myth of the private individual, the demolition of nature, the erosion of public life, the death of Europe’s peasantry – comes into a new focus. The skulls on the table are no generic memento mori. They are our ancestors.

Read on: Saul Nelson, ‘Opposed Realities’, NLR 137.