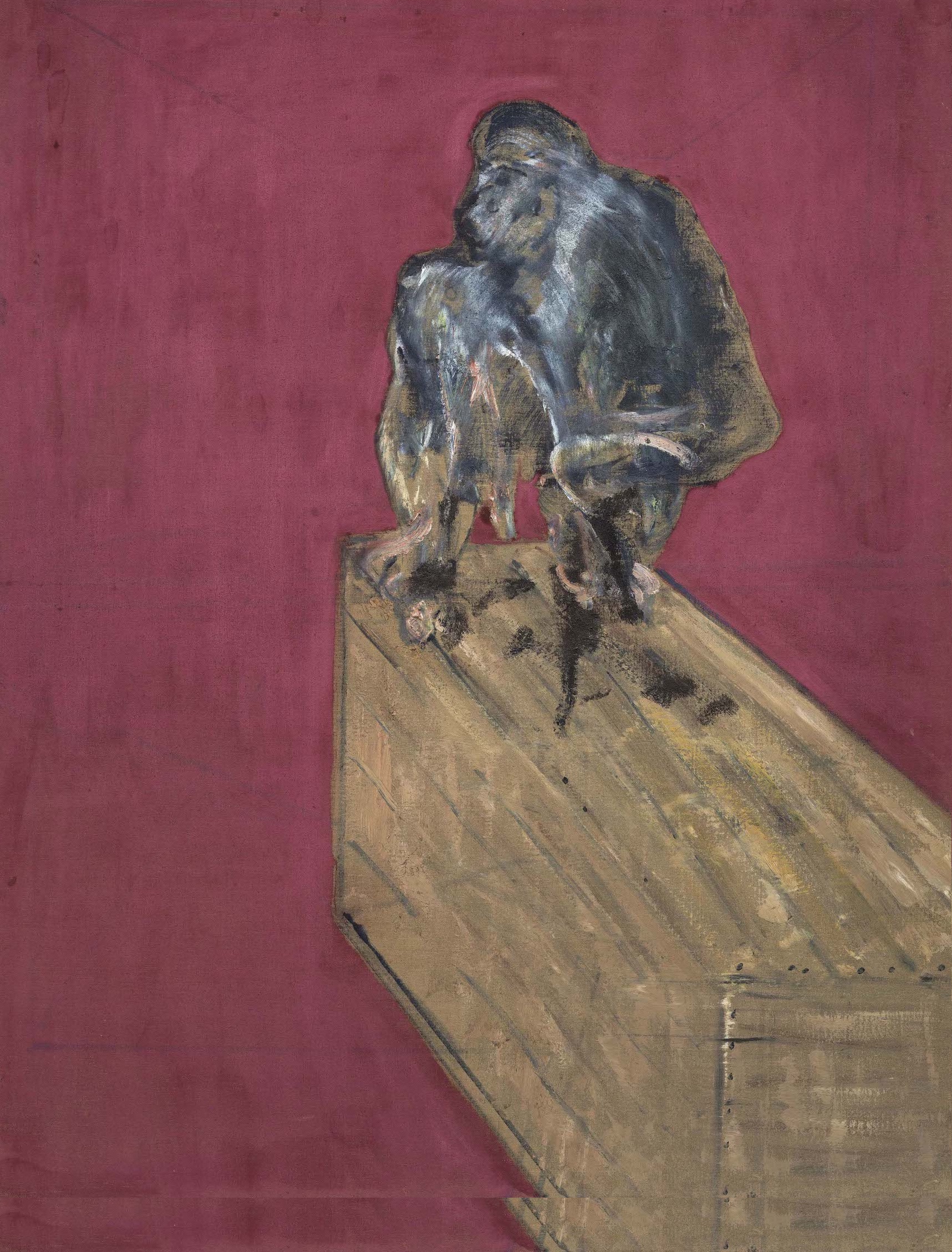

Has there been a modern painter more obsessed with animals than Francis Bacon? The third room of Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, the vast, frustrating, often brilliant exhibition soon closing at London’s Royal Academy, is titled ‘Wildlife’. It is a menagerie. There are monkeys; owls; two greyhounds sprinting round a racetrack; a chicken carcass with a chimp’s mouth nailed to a crucifix; a dog pulled by a leash; another panting in the heat. Dog (1952), on loan from the Tate, delights in the surface shine of fur under sun. It is a marvel of sustained attentiveness, not just to the way that bodies react under heat and duress, but to the peculiar synergies between such observations and the material of oil paint. The face is endlessly reworked; thinned and smeared with rags and turpentine, the paint forms shadows that spill from the body and pool on the ground. By comparison, the rest of the painting has no density. The little cars that zip across their coastal highway in the background; the thin blue horizontal line for the sea; the ridiculous miniature palm tree; the massive stretches of empty, unprimed canvas that stand in for earth and sky: each of these devices insists on its own emptiness, on the artificiality of the painted image. Dog displays two sides of modernist art: at once sceptical of art’s connection to sensory experience, and utterly besotted with it.

Bacon is one of very few artists whose commentaries on their own work are better than anything else that has been written about them (Matisse is another). He knew what he was talking about when he told the critic David Sylvester, adapting a phrase from Valéry, that he wanted ‘to give the sensation without the boredom of its conveyance’. In Landscape near Malabata, Tangier (1963), the sprinting dogs are blurs. A foreleg bends back and upwards as it slaps off the turf. Force is conjured out of a single thinned smear of mixed cream and black paint. Curved shadows veer around the left-hand side of the track, like tyre-marks left by a race car. These touches are extreme, even crass. There is something cartoonish to Bacon at his best. The paintings show a love of exaggeration that extends from their brilliant colours to their use of citation. He never lost his early fascination with impressionism. The landscape behind the dogs, with its bouncing pink grasses and crazily leaning tree, is like something out of the kitschiest Renoir.

There was more to painting animals than immediacy. The hang in the RA’s third room makes a claim for what the stakes were. Beside Landscape near Malabata is a work made five years earlier, Figures in a Landscape (1956-7). Both paintings place their figures within a centrifugal armature, a broad, circular ground that sweeps its contents into motion. Both make beautiful landscapes out of the remnants and constraints of cubist space. But in place of dogs sprinting, Figures in a Landscape gives us two men, one crouched and reaching between the knees of the other where they poke up from the deep grass. Dogs and men; man and beast; the greyhound race and the sexual tryst in the park – with such equivalences, we arrive at the exhibition’s argumentative crux. The basic question it poses is this: how deep, for Bacon, did the analogy go? All the way down? Did the basic animality of human existence imply no substantive difference between human and animal life? These are difficult questions, and I do not think Bacon ever arrived at satisfactory answers. Whenever he pretended that he had, the results were not auspicious. A painting like Two Studies from the Human Body (1974-5) shows the risks. Its Darwinism is obtuse. The figure in the foreground swings his knuckles like a gorilla. Fur sprouts on the side of his body. His mouth has a rat’s tooth. Behind him, a trapeze artist dissolves into primordial ooze. Gone is the precision that had stretched the surface of a painting like Dog as tight as a drum. In its place a plangent existentialism – affirming the brute in man! – takes centre stage.

Two Studies from the Human Body shows Bacon on autopilot, imitating himself. It comes from a later phase in his career, when he was already feted, imitated: recognised, along with Lucien Freud, as the greatest painter of his generation. He painted better when he allowed for more ambiguity. In the trio of paintings titled Study for Bullfight (1969), united here for the first time since they were made, the bull’s pirouette conveys the spiral logic of each painting – from the circular arena within which the contest takes place to the thematics of human brutality that encompass the spectacle. There is panache to the curators’ decision to hang these canvases on three sides of the gallery’s central rotunda. Their spacing forces the viewer to pace in a circle, like one of the bulls lunging after its matador (though I still wished for the chance to see the three images side by side on the same wall, if only to get them all in view at once). In each painting it is the distance between bullfighter and bull that is at issue. Often there is little to speak of. In Study for Bullfight No.1 the line of the bull’s motion connects directly with the matador’s chest. His features are whipped sideways, lips puckered as if he had been punched. In Study No.2, the man seems to have the upper hand in the contest; there is enough space between him and the bull for his rear to come into view. In the final Study there is little doubt that the bull has bested the man. The human body melts away before the horns. The face is a grim shadow. Bacon made frequent use of Nazi imagery – photographs from Nuremberg shared space on his studio floor with those of rhinoceros and x-ray patients. The screen-like towers behind the first two Studies show figures from the rallies as if from a Leni Riefenstahl reel. The presence of a crowd of baying national socialists suggests one more twist in the knot between man and beast; Nazism was the ultimate historical instance in which the pursuit of social Darwinism tried to transform human beings into animals. But the figures are ghosts; they flicker as if in projection. The swastikas are hollowed out. They suggest a different register of experience, besides and apart from the heat of the bullfight.

Like so many modernists (Goya, Picasso, Hemingway…), Bacon was drawn to the bullfight because it mixed sex with death, erotic display with ritual killing. In such images, he took up the more brutish aspects of human existence, but in such a way as to paradoxically highlight those orders of experience that are not reducible to animality. Violence and sexual pleasure might be felt by human and animal alike; but they are lived differently. Take Figures in a Landscape once again. The posture of the crouching man is simian, his spine elongated. The way he reaches out an arm while tucking his face into his armpit has something in common with the ape man of Two Studies. Naked, Bacon’s figure takes refuge in the crevices of his own body. His legs are tensed as if to hop. But the impetus for such concealment could not be further from the animal world. Chimpanzees do not hide themselves in order to copulate. Plunged in the multicoloured grasses, Bacon’s two figures pursue a desperate secrecy. And that secrecy, that fugitive intimacy, is part of their humanity, part of their belonging to a complex, social world of norms, prohibitions, and repressions. Transgression – the expression and performance of forbidden desire – is policed in this social world. Yet it is also realisable; the policing is never absolute. There is an unspeakable gentleness to the manner in which the lowermost man in Two Figures in the Grass (1954) turns his head towards his lover’s. Nose touches ear. The painting’s rendering of the human body as a mass of heaving muscle takes on new meaning as a result.

Bacon told Michael Peppiatt that before deciding to become a painter he spent his early twenties in Paris reading Nietzsche. It was Nietzsche who wrote of the ‘painful embarrassment’ posed to humanism by Darwin’s discoveries, Nietzsche who gave fullest recognition to the challenge offered to all elevations of humanity by our common animal heritage. But he also saw distinctions. In his second Untimely Meditation, Nietzsche wrote that:

the animal lives unhistorically: for it is contained in the present, like a number without any awkward fraction left over; it does not know how to dissimulate, it conceals nothing and at every instant appears wholly as what it is; it can therefore never be anything but honest. Man, on the other hand, braces himself against the great and ever greater pressure of what is past: it pushes him down or bends him sideways, it encumbers his steps as a dark, invisible burden which he can sometimes appear to disown and which in traffic with his fellow men he is only too glad to disown, so as to excite their envy.

A self-proclaimed ‘latecomer’, Bacon knew what disowning human history could amount to. He was conscious of arriving at modern art in the wake of its great innovations – separated from its triumphs by the gulf of a disastrous war. Each one of the 45 paintings in this exhibition reveals a preoccupation with art history that goes far beyond the usual citations of Velázquez and Muybridge. History mattered to Bacon, and it worked in the opposite direction to animality. His Nuremberg figures loomed large for a reason – they are visions of a society hell-bent on ‘natural order’, a totalitarian social organisation in which the state holds secrets, but its citizens have none. In their fugitivity and dishonesty, in their (temporary) disavowals of their own animality, his human figures reject such enforcement. They are redoubts against the nightmares.

Read on: Julian Stallabrass, ‘The Hockney Industry’, NLR 73.