On 19 September, Russia’s three-day elections ended with the expected result – United Russia (UR), the Kremlin’s party, yet again won a constitutional majority in the Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament. Since its formation in 2001, the party has always held a majority of seats. Though elections in Russia are neither free nor fair, the results are not 100% falsified either. The regime’s political operatives need to ensure the UR’s resounding victory every time without losing the air of credibility. During this electoral season, the challenge was particularly tough: UR’s popularity, even according to the official surveys, stood at barely 30%: not nearly enough for a simple let alone constitutional majority. Nevertheless, the party won 324 seats out of 450, only 19 less than in 2016. For this result, credibility had to be sacrificed – and it was.

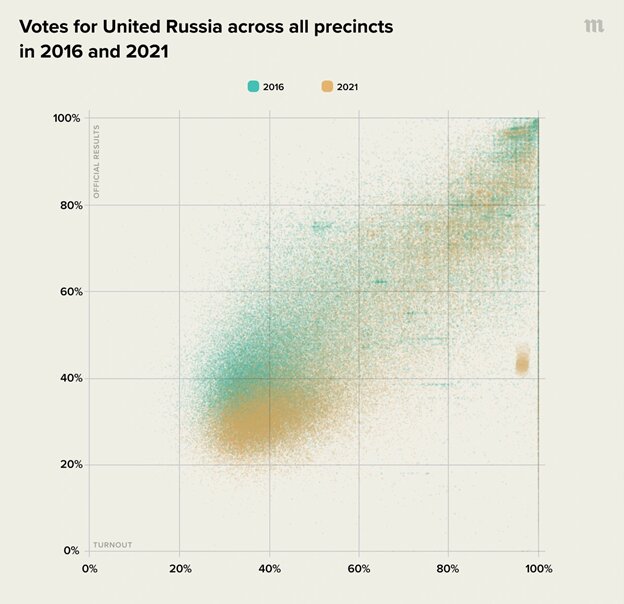

The scatter plot above is the simplest visual proof of widespread electoral fraud in Russia. The dots represent individual electoral precincts, with the X axis showing the turnout and the Y axis the share of the UR vote. The comet-like shape indicates a strong correlation between the turnout and the vote for the Kremlin’s party – the higher the turnout at the precinct, the more votes are cast for UR. The comet’s ‘head’ – a dense cloud of dots – unites the precincts with more or less honest results. However, the ‘tail’ comprises the precincts with irregularities. There is only one way of explaining such a strong correlation between the turnout and the UR vote: ballot-stuffing of various shapes and sizes (the photo and video evidence of such practices is, of course, abundant). In fact, the dots in the top right corner of the plot are the precincts where both the turnout and the UR vote are close to 100% – the results there are falsified in their entirety. Such precincts are mostly located in the so-called ‘electoral sultanates’, where fraud is particularly widespread. Most of the Caucasus falls into this category.

Detecting fraud is not the only use of the scatter plot shown above. It also allows us to glimpse the real results of elections. The center of the comet’s head approximates the national turnout and votes for UR that were unaffected by fraud. Since the last election, held in 2016, the comet fell – that is, real support for UR declined by some 10 points, from 40% to 30% (a figure that corresponds to the pre-election polls). However, the official results did not decline nearly as much, suggesting that the scale of fraud has dramatically increased since 2016, perhaps to an all-time high.

Organic support for the regime is waning. After a decade of economic stagnation punctuated by deep crises, the government is out of ideas and has no vision for the future. The ‘rally-behind-the-flag’ effect of the Crimean adventure has disappeared, and the pain of austerity measures, particularly raising the retirement age in 2018, has been felt by the population. In this unfavorable conjuncture, the Kremlin was forced to hold elections that were particularly significant for its future: the Duma elected this September will preside over Putin’s attempt to reelect himself as president in 2024. Its failure to secure a landslide might exacerbate the ‘problem of 2024’, which is by far the most important obstacle for the regime. Gauging this, the Kremlin has acted increasingly brutally and erratically. Alexei Navalny was poisoned and then imprisoned, his organization banned as ‘extremist’; multiple independent media outlets have been closed; opposition activists have been sent to prison or into exile. The elections were held over three days, creating additional opportunities for fraud. The Kremlin’s strategy was to mobilize state-dependent groups such as public employees and workers at state-owned factories while avoiding high ‘real’ turnout that could result in a protest vote.

UR launched its campaign last spring by holding so-called ‘primaries’. Their official purpose was to identify the party’s strongest candidates in single-member districts, yet in reality this allowed them to test the capacity of the vast administrative machinery to coerce votes. State workers were forced by their bosses to register as participants in the ‘primaries’, which eventually attracted 12 million voters (half of them by electronic voting). This figure was already more than 40% of UR’s performance in the previous parliamentary elections. Thus, UR needed about 15 million more votes to reach its target and regain its constitutional majority (at least 300 deputies). With the party’s rating steadily declining, success could only be ensured primarily by a further expansion of compulsory voting.

To boost support for UR, which in the eyes of most Russians is associated with declining living standards and increasing repression, its party list was topped by two of its most popular members of the government – Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu. In August, the government also made a one-off payment of 10,000 rubles (117 euros) to pensioners and families with children, which the state media portrayed as an initiative of the ruling party. The main message of UR’s election campaign was the need to maintain stability, since any attempt to challenge the status quo would only worsen the situation and be used by external enemies to weaken the country.

The elections thereby became a quasi-referendum where voters were enjoined to either accept or reject the current regime. In this binary system, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF) finally became the most obvious way to register dissent. Despite the traditional conformism of its leadership and its close contacts with the Kremlin, the KPRF was the most oppositional of all parliamentary parties in the previous Duma: the only one to consistently vote against the unpopular pension reforms of 2018 and the amendments to the Constitution in 2020 that allowed Putin to be re-elected as president for two more terms. This position has attracted new voters to the KPRF in recent years: residents of large cities, disenchanted young people and the educated middle classes, for whom the KPRF’s traditional ideology – a mixture of Stalinism, nationalism and social democracy – mattered less than its insurgent energy. The emergence of this new electorate has also transformed the party’s rhetoric (which is increasingly focused on democracy and social justice) as well as its cadres. Over the past few years, a number of bright young party leaders have sprung up in different regions of the country, marking a rupture with the old image of the KPRF as an archaic fragment of the Soviet state apparatus.

In Saratov, for example, Nikolai Bondarenko, 35, a member of the local KPRF leadership and one of the most popular political vloggers in Russia, ran as a candidate in a single-member district. His YouTube channel, which has more than 1.5 million subscribers, features live reports from protests and regional parliament sessions, where Bondarenko regularly confronts the UR deputies. The authorities made exceptional efforts to prevent Bondarenko from entering the State Duma: his supporters and election observers were constantly detained by police. Bondarenko ultimately lost to a little-known UR functionary from Saratov. Meanwhile, in the northern region of Komi Republic, local KPRF leader Oleg Mikhailov, 34, managed to defeat his UR competitor after coming to prominence as one of the figureheads of a protest against the construction of a huge landfill site. In Moscow, the KPRF backed the candidacy of a university trade union activist, 37-year-old mathematician Mikhail Lobanov. His campaign was supported and staffed by members of radical left-wing groups such as the Russian Socialist Movement. Lobanov, who openly describes himself as a democratic socialist, was able to draw support from a wide range of voters and mount a forceful challenge to his UR opponent, a well-known propaganda talk-show host on Russian TV, whom he beat by 12% (more than 10,000 votes); though the victory was eventually stolen by UR’s electoral fraud.

One of the main problems for the Kremlin during this electoral season was the ‘Smart Voting’ strategy proposed by Alexei Navalny two years ago. The essence of this strategy was to identify UR’s strongest opponent in a single-member district and urge all opposition voters to support this candidate regardless of her party affiliation, with the singular goal of decreasing the number of seats available to UR. With the ruling party’s credibility steadily declining, Smart Voting has become a serious threat to UR’s chances of winning a constitutional majority in the new parliament. Russian security agencies made enormous efforts to block all web pages that offered Smart Voting recommendations (even Apple and Google were forced to comply and remove Navalny’s phone apps a few days before the election). Nevertheless, Smart Voting lists, most of which were occupied by the representatives of the KPRF, circulated widely on the internet. In numerous videos, Navalny’s supporters endorsed the KPRF on a party-list vote as the only opposition party guaranteed to pass the 5% threshold for parliamentary representation.

When the first election results were published, based on voting at regular polling stations but not on electronic voting, they showed a huge increase in support for the KPRF, whose candidates stormed to victory in a number of single-member districts. In Moscow, candidates from the KPRF and the liberal Yabloko party won 8 out of 15 districts. In Moscow as a whole, the KPRF took first place on the party lists, receiving 31% of the vote (while the UR got 29%). However, the next morning, when the results of the electronic voting were made public, the picture was inverted: UR was now the winners in all of Moscow’s single-member districts, with an outright victory on the party lists. Electronic voting proved to be the Kremlin’s trump card, enabling them to manipulate the outcome in their favour.

Still, even after all the Kremlin’s machinations, the election results showed a major increase in support for the KPRF. Compared to the previous election, the party received 3 million more votes and finished second behind United Russia with 18.9%. In four regions (Khabarovsk Area, Yakutia, Mari El and Nenetsky Autonomus District), the KPRF came first, overtaking the ruling party. Despite UR’s official victory (49.8% for the party lists and 198 seats out of 225 in the single-member districts), its position is weaker than ever before. Without voter coercion and fraud, it is now unlikely to win a majority. Further losses of support will push the authorities towards openly repressive methods and accelerate the regime’s mutation into an outright dictatorship.

The other main outcome of the election was the success of the Communist Party, which finally became Russia’s main legal opposition force. By contrast, Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s right-populist LDPR abandoned its image as a protest party and lost almost half of its vote (7.4% compared to 13.1% in the previous election). The new position of the KPRF will inevitably activate an internal contradiction between the old leadership, accustomed to acting within the limits set by the Putin administration, and the younger generation of activists, determined to transform the KPRF into a mass party of non-parliamentary protest. The radical left, which has always viewed the party as a conformist remnant of the Soviet bureaucracy, incapable of militant, independent politics, will have to adjust its approach as well.

Read on: Tony Wood, ‘Contours of the Putin Era’, NLR 44.