Amy Winehouse has been dead for almost eleven years now. Her work is unforgettable. Still, the complexity of that work, and that story, tends to get lost, dispersed and then reduced, wrapped up tight, a small pellet of abject, glamorous pain. Traces of Amy remain indelible: a lyric, a phrase and always an image: derived from a photograph, it’s nevertheless recognizable as a silhouette, outlined in black and white. At the beginning of her career, Amy chose to be instantly identifiable, with an expansive hair-do and intense eyeliner marking out a look that was hers alone. It was a quotation and an exaggeration, like a logo or a joke. The repeated and repetitive story goes like this: Amy Winehouse was a singer who achieved great fame very quickly and made a lot of money, and it killed her. Or she killed herself. Or drugs and alcohol killed her. Her dominating father killed her, or was it that boyfriend? (She wouldn’t go to rehab, right?) No, no, no.

‘Paparazzo’ is the name of the fictional street photographer who follows Anita Ekberg, Anouk Aimée, and Marcello Mastroianni, the tabloid journalist, in La Dolce Vita, Federico Fellini’s film of 1960. This name (which in Italian has a connotation of something that buzzes around you, like a wasp or a mosquito) was quickly re-functioned as a nickname for aggressive photographers who chased celebrities, looking for a shot they could sell to the increasing numbers of cheap celebrity papers and magazines. A symbiotic relationship between the paparazzi and their targets quickly developed: 1960s photos of Sophia Loren, and others, pausing to pose in the street for the camera, prove it was always thus. Still, the classic paparazzi photo is by definition unposed, non-consensual, sudden and almost violent in its capture of the subject, denying the star the right to walk down the street unseen. It’s an interruption and an idealization at once.

Photographer: Morgan Waltz

In 1969 Jacqueline Onassis told her secret service people to ‘smash the camera’ when Ron Galella, the paparazzo who pursued her every day, leaped out of the bushes to photograph her nine-year-old son riding his bike in Central Park. Galella sued, Jackie counter-sued, and the court determined that in future he had to stay 25 feet away from her, and 50 feet away from her children. In other words, with a zoom lens, Galella still had visual access to the most famous woman in the world, while she was protected from immediate physical proximity. A photograph of Galella approaching Jackie with a huge measuring tape makes fun of this restriction; his comment in court that he thought that his constant unwanted attention would distract Jackie from her grief is particularly bleak. Widowhood is no protection.

Diana Spencer’s death in Paris in 1997, almost thirty years later, crashing at speed very late at night while driven by a drunk chauffeur in a limousine to avoid paparazzi chasing them on motorbikes, provides the narrative closure to this classic story. It’s an old story, about a beautiful woman who wants something, some kind of recognition, and gets so much of it that she can’t leave her house. It’s a fairy tale of some kind, where the punishment is to have too much of what you want: money, fame, recognition. It’s about being turned into an image, an image that itself becomes transformed into a commodity, to be consumed by millions, when maybe all you want these days is some kind of a life.

Bedros Yeretzian’s recent show at Commercial Street in Hollywood presented seven silkscreen enamel prints on aluminium, placed flat against the walls of the space. Each was taken from a paparazzi photo of Amy Winehouse, who seems almost ghostly, moving in and out of definition as we move through the space. As we get closer to the work, she dissolves: we find ourselves looking at a translation of a print image into something like text, or maybe it’s a translation of something like text into an image. The work tips back and forth, as we close in and recede, proposing a temporary equivalence.

Photographer: Morgan Waltz

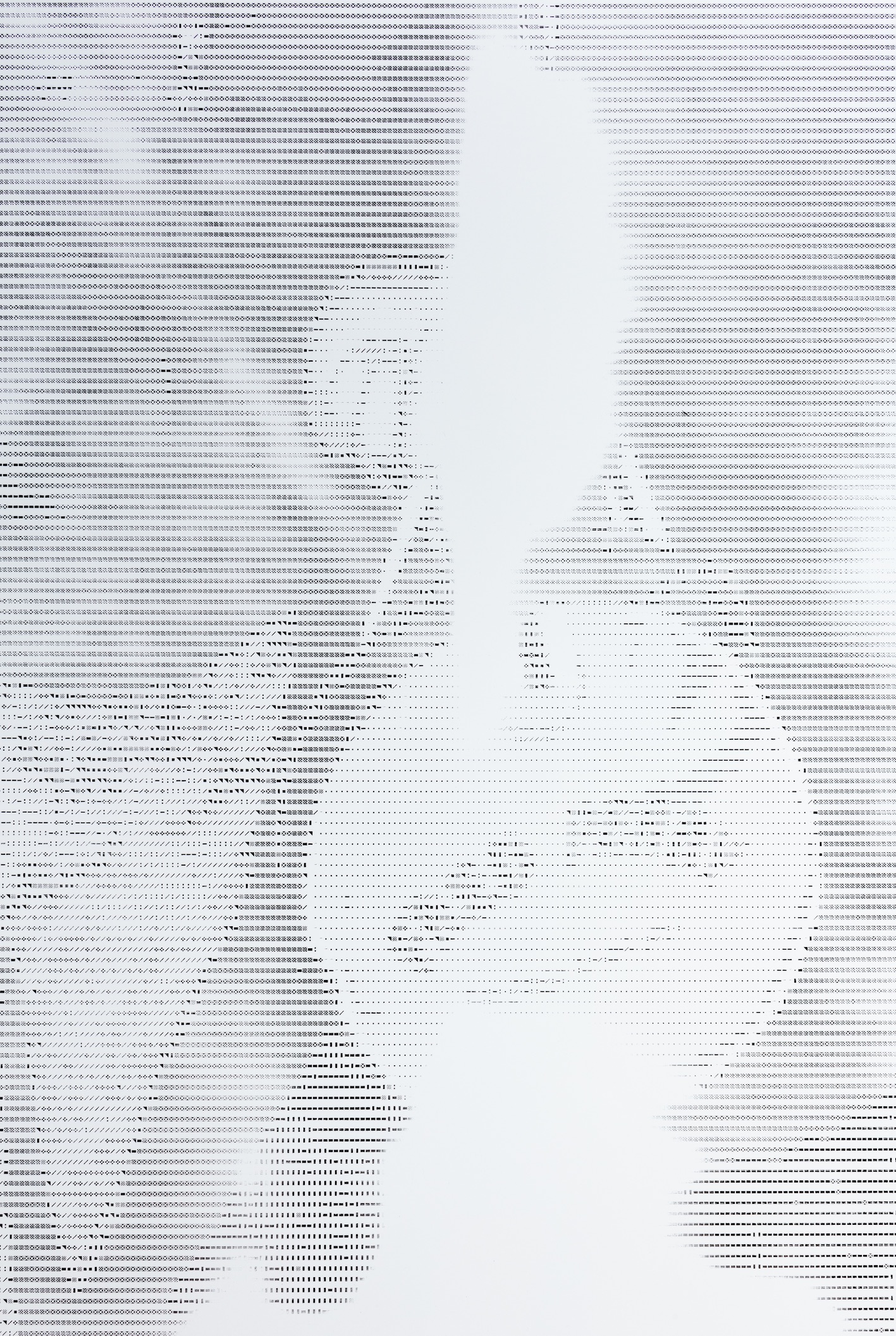

This is an ASCII image, evoking early computer printers that ‘lacked graphics capability’, so images were constructed (along with other graphic patterns, like text breaks) out of text itself, using the limited resources of fonts arranged in non-linguistic ways. American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) images date from the early 1960s, although some forms of poetry had for centuries made use of the possibilities of print (and, later, typewriters) to distort and construct meaning through shaping printed text on the page. Looking at these images of Amy, we first see that the picture is built out of code, in a throw back or shout out to the 1960s, our digital heritage, and then that the code is not the dots, dashes, punctuation marks, and letters of a conventional typeface, but another kind of code altogether. Turning to the minimal information provided by the artist, we discover that this ASCII image-generator is using an open-source typeface that ‘simulates the International Code of Signals’, a communication system using a limited number of flags with simple geometric patterns to send messages between ships. The International Code of Signals was ‘originally developed in the 1850s by the British Board of Trade.’

So this is about translation, a series of transitions from a living body (belonging to Amy Winehouse, before her death in 2011) to spontaneous, unposed photographs in public spaces (the language of paparazzi photography) that are subsequently put through an automatic ASCII image-generator (an online resource) using a specific font (sourced from dafont.com) that was adjusted to make the font fixed-width (otherwise ASCII won’t work) that itself derives from and simulates the International Code of Signals. Each move inserts a level of distinction and difference into the system of representation. Each shift takes me further away from Amy Winehouse and closer to an analysis of power and violence.

The image of the woman (recognizable, mediated through paparazzi photos) dissolves into something called code (also recognizable, but unreadable), a set of signs functioning as an obstacle rather than a vehicle for meaning. It’s a liminal space, hovering, referencing the capacity of code to capture information at the same time as it refuses to relinquish it, to release meaning into the void. We find ourselves suspended in a zone of uncertainty – with Amy’s iconic image always in play, stabilizing and destabilizing in turn. We move closer, she fragments, the detail of the code pops out; we move further away, she appears, in a shadow form and the code becomes imperceptible. When I’m staring at an image and I know it’s made out of code, a code that’s out of reach, my mind goes to my phone, so close at hand. I’m looking at images of women on my phone all the time, and I know that image is made out of code, zeros and ones, they tell me, and I can’t read that, I can’t even perceive it, I can only see the image it presents. This is a description of Instagram, where we live now.

Photographer: Morgan Waltz

This particular code, the International Code of Signals, belongs to the history of the British colonial project, dating from the mid-nineteenth century, before radio waves changed our world. A way of communicating that is imbued with both trade and war, the code was standardized to allow different fleets to signal typical messages (such as location and status) to each other, through combining flags in specific sequences. At the same time, the entire set of flags stands in for the alphabet and the numbers zero to nine, with a coded capacity for repetition that removes the need to have multiple sets of flags. Individual flags are used for emergency messaging and simple responses, like yes (‘C: Charlie’) or no (‘N: November’). N and C together (no and yes) functions as a distress signal, a fundamental binary undone or confused constituting a call for help.

It is a code that precedes our digital world yet in some ways predicts it. And gradually a sequence unfolds: the image of the woman, the star, presented as a site where money is made (trade/capitalism), where her subjectivity is taken over and commodified (colonialism), where her rage and pain are spectacularized (war). Still, unlike some maritime experts, I can’t decipher this code: I am situated by the work in a position that is both open and restricted, at the limits of meaning. I’m inside a system that I can’t take apart (like my phone), up against the invisibility and illegibility of capitalism, war, the colonial project, each of which are everywhere and nowhere. (They are the air we breathe.) And it is the image of the body of the woman that holds these contradictions.

Here this code has been subjected to the logic of the ASCII image: by turning the International Code of Signals into a digital font, it has been subsumed into another system entirely. Even if someone came into the gallery with a magnifying glass and could ‘read’ the lines of flags across the images, it would not make any sense. The dominant system of representation is the photographic image itself, while the capacity for these geometric flags, carefully arranged in sequence, to communicate messages between floating bodies persists only as a trace, a material implication. There is no secret message buried in Amy’s Fred Perry handbag, I think.

Photographer: Morgan Waltz

Nevertheless, the title of the show, Enemies, opens up a set of questions about language and the image; while we recognize ASCII as a quotation from another era, the early digital, here it incorporates another archaic language system, the symbolic flags of the maritime world. The singer’s image floats within a contested space, delimited by the overlapping co-operations of these two sign systems, an image that itself construes more explicit scenes of conflict: the endless battle played out between paparazzi and star, the struggle for so-called self-determination carried out by the singer herself. Arguably paparazzi photography is a sign system also: there aren’t two signifying systems producing a third thing, the image; it’s the encounter of at least three distinct systems producing something like the skeleton of an image.

Enemies holds these different histories and ideologies in suspension, in a kind of stalemate, or a recognition that the various subjects of the artwork may be dispersed among them, while inviting us to recognize our own participation, as viewers, or critics, and the artist too, hanging out together in a state of hostility. There’s a quiet suggestion that the only aesthetic move that remains is to overlay various different more or less unintelligible semiotic systems, intending thereby not to cancel them out, nor to decode them, but on the contrary, to expose the multiple ways that their automatic operations determine our inner and outer landscapes, in a kind of relay that moves in perpetual circles, never landing on a conclusion.

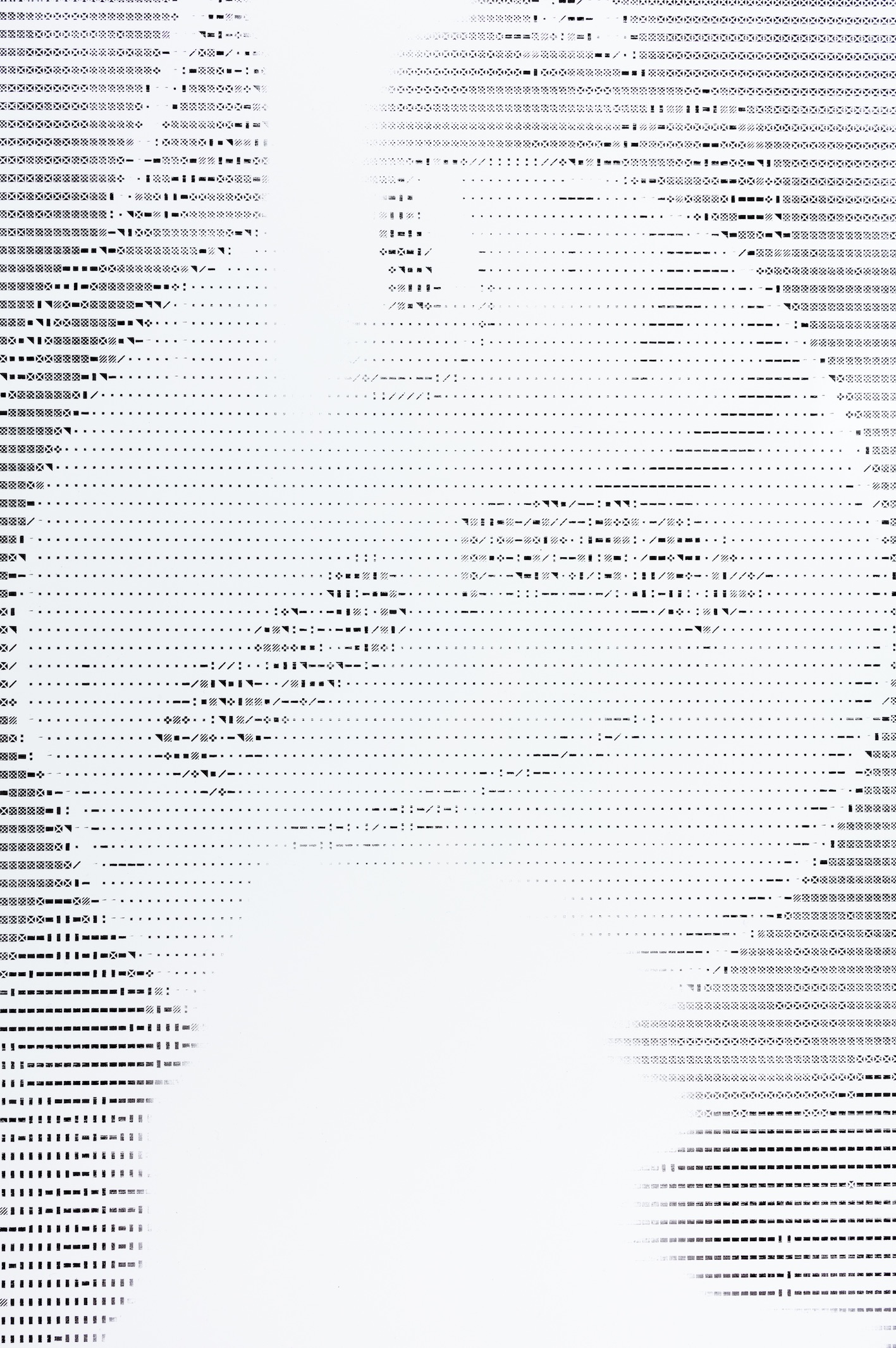

And then the whole thing warps, turning inside out, revolving again. Because hey, these images were made by hand. The silkscreened enamel on aluminium is flat and hard, slightly reflective, recalling the qualities of manufactured objects. Still, they’re imperfect, or maybe it would be more accurate to say they are almost perfect, just shy of perfect. Traces of the gesture, the specific instance of the pull of the squeegee across the screen, registers another body, an indexical mark buried within the photographic remains. Someone made this thing: an unrepeatable moment in time, like the grain of the voice in Amy’s recordings. The counterpart lies in the grain of the screen print, haptic (we want to touch the surface) and alive, returning us to a memory of a living body that is precisely not an image.

In sensing these physical movements in the imperfection of the image, we participate in another, more ancient, coded system, one that we read with our own bodies. The imperfect gestures leave gaps in the coded image, areas of emptiness, suggesting the incompleteness of our digital world, where the living body is itself signified in negative, in absence, in lack. Amy Winehouse is dead. The body that exists in the work is not hers, and it presents, through failed gestures, as an absence within the image. Such small failures and imperfections may recall Warhol’s Marilyn, his Jackie, the intentional slight mis-registration of the silkscreens that left traces of an imperfect body in the image of a goddess. And maybe an embodied imperfection, incompleteness, can evoke what it’s like to be alive, and therefore soon to be dead, more profoundly than any photograph.

The embodied gesture of the pull, making the image, reminds me that Amy is not alone – Marilyn, Jackie, none of them is perfectly solitary in their apotheosis. There’s another body there, at least one and maybe, probably, more than one, doing the work of remembering. It’s the one who made the image, a kind of exchange between the goddess, star, celeb, singer, queen, and the one over here, on our side of the equation, fan, photographer, image maker, consumer, archivist. The one building the memorial, remembering the flaws, marking the absences and the remaining traces of something lost and gone.

Photographer: Morgan Waltz

More than one, yes, because it seems like an implicit collectivity is built into the material forms this artist has chosen. It’s partly a result of the ready-made effects of the open-sourced, free software – ASCII, the International Code of Signals, dafont.com – put together with the proliferating subjects belonging to the project of paparazzi photography. And there’s an automatic dimension here, again recalling Warhol; the screen print is itself mechanical in its implicit aspiration to a perfectly smooth surface, and the paparazzo too, perhaps, automatic in his unhesitating exploitation of the moment. The artist surrenders to the apparition, the collectively invented ready-made, glad of the respite. Certain forms of artistic agency, valued in a romantic context, are rubbed out, erased by the pressure of public, downloadable formats and their operations. Among this cloudy multitude, Amy appears, angelic.

Still, despite everything, these pictures return me to a bodily reality, recalling simple things: there’s no ideas without chemistry, signals moving around that fleshy brain lump in my skull, no conversations without a heartbeat and a wish. (Death is very close.) In the gaps that opened up within these representations, recognizable and unrecognizable at the same time, in the search for clarity and connection, people in the gallery, encountering Bedros Yeretzian’s work, pulled out their phones, using them as a viewing device, to produce another level of legibility. The phone cameras changed the image, intensified it, making it more accessible, more coherent, less dispersed. A phone snapshot of an artwork is a memory aid: curiously, in this case the mediation of the phone resulted in a temporary clarity, artificial, itself contaminated by the logic of a code whose operation I do not understand. In this layering of code upon code, another body is manifest, the digital ghost of Amy Winehouse.

She’s no longer with us, yet she’s everywhere.

Read on: Julian Stallabrass, ‘Sublime Calculation’, NLR 132.