Mounted police charge striking workers, battering them as they try to flee. Children in threadbare coats watch the pandemonium, transfixed; women clutching swaddled babies look on. It’s as though a riot has broken out amidst the milling, workaday calm of Lowry’s Street Scene (Pendlebury). The American artist Alice Neel (1900-84) painted Uneeda Biscuit Strike (1936) at the peak of Depression-era labour militancy. The pictured strikers were employees of the National Biscuit Company, and the painting’s political message is, at first glance, clear-cut: support the workers. Its ostensibly polemical intent makes it easy to dismiss the work as a ‘bad’ painting – as unsophisticated and didactic. Yet its complex composition, on a closer look, is harder to grasp than its message.

Consider another painting from the same year, depicting a march in New York. It’s a dense dusk in May. The lights are on in the lofts and cold-water apartments on either side of the street. A column of rank-and-file Communist Party members and fellow travellers filter towards the vantage point that we, the viewer, now occupy. It’s as though we are among the crowd and have turned back to survey our fellow demonstrators, who carry luminescent hammer-and-sickle banners aloft like Chinese lanterns. In the foreground, we find ourselves face to face with four men, at the vanguard. One of them – the Welsh poet Sid Gottcliff – holds a white placard whose text gives the painting its title: ‘NAZIS MURDER JEWS.’ When Neel showed the work at the American Contemporary Art Gallery, one critic deemed it ‘an interesting picture, but the sign is too obvious.’ Neel’s response was characteristically curt: ‘But if they had noticed that sign, thousands of Jews might have been saved.’ The ACA’s director Herman Baron agreed, noting that ‘drawings and paintings can fight too.’

Uneeda Biscuit Strike and Nazis Murder Jews are currently on show in ‘Alice Neel: Hot off the Griddle’ at the Barbican (until 21 May). Visitors have likely been drawn by Neel’s celebrated later portraits of expectant mothers, feminist critics, inter-racial partnerships, drag queens, and poets and artists such as Frank O’Hara and Andy Warhol. (‘I always loved the working class and the most wretched’, Neel reflected at the end of her career, ‘but then I also loved the most effete and the most elegant.’) But the tensions discernible in these two early paintings provide an instructive framework through which to see, or read, an Alice Neel painting, and perhaps also a framework through which to understand the evolution of her subject matter and style.

The Barbican retrospective makes clear that Neel’s was ‘a lifelong commitment’ (the phrase is the name of one of the exhibition’s final rooms). Yet her commitment took various, sometimes conflicting forms. She was steadfastly devoted to her project – unfashionable in the age of Abstract Expressionism – of representing people with her signature combination of uncanny vividness and freewheeling acuity. And she was also committed to social causes, from unemployment and union organization in the 1930s, to women’s liberation in the 1960s and the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. In exploring the interplay between Neel’s commitment to politics and to portraits, ‘Hot off the Griddle’ probes the limits of realism as a means of political expression.

Neel was born in 1900 (she was ‘three weeks younger than the century’ as she liked to say). Difficult years spent in and out of psychiatric hospital and the loss of two daughters by the age of thirty (one to death from diphtheria, the other to forced adoption by her husband’s disapproving upper-class family in Havana) were followed by years of increased stability, if never luxury or tranquillity, in which she balanced her career with raising two young sons as a single mother. In the 1970s, two sea-changes – second-wave feminism and the development of postmodern critiques of Abstract Expressionism – converged on the art world, creating a wave of interest in women artists and figurative painting. In 1974, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York staged a major retrospective of Neel’s work – the only show of such scale held in the US in her lifetime. In 1981 Phillip Bonosky, along with the Artists’ Union, organized an exhibition in Moscow, the first solo show of an American artist held in the Soviet Union. (‘I always wanted to exhibit in the Soviet Union, because I believe utterly in détente’, Neel said. ‘I always thought it would be a great thing for the Soviet people to see the American people as I see them.’)

Two travelling retrospectives have brought Neel to audiences across the US and Europe in the last eighteen months. People Come First opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York before moving to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, then the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Un Regard Engagé was on show at the Pompidou Centre – and was broadly similar in scope and works to the Barbican exhibition – and will travel to the Munchmuseet in Oslo later this year. Though these exhibitions were organized in collaboration with each other, they have had different designers and architects, and the paintings have been accompanied by different texts: each city has received a different version of Neel. If the Met gave her something of a DNC makeover – portraits of cultured New York liberals, figured as a diverse set of individuals, unmoored from society at large – then the Pompidou dragged the artist back to the barricades: ‘Radicale! Politique! Humaniste! Féministe!’ read the online advertisement. It is this latter version of Neel that has travelled to the Barbican, under the curation of Eleanor Nairne.

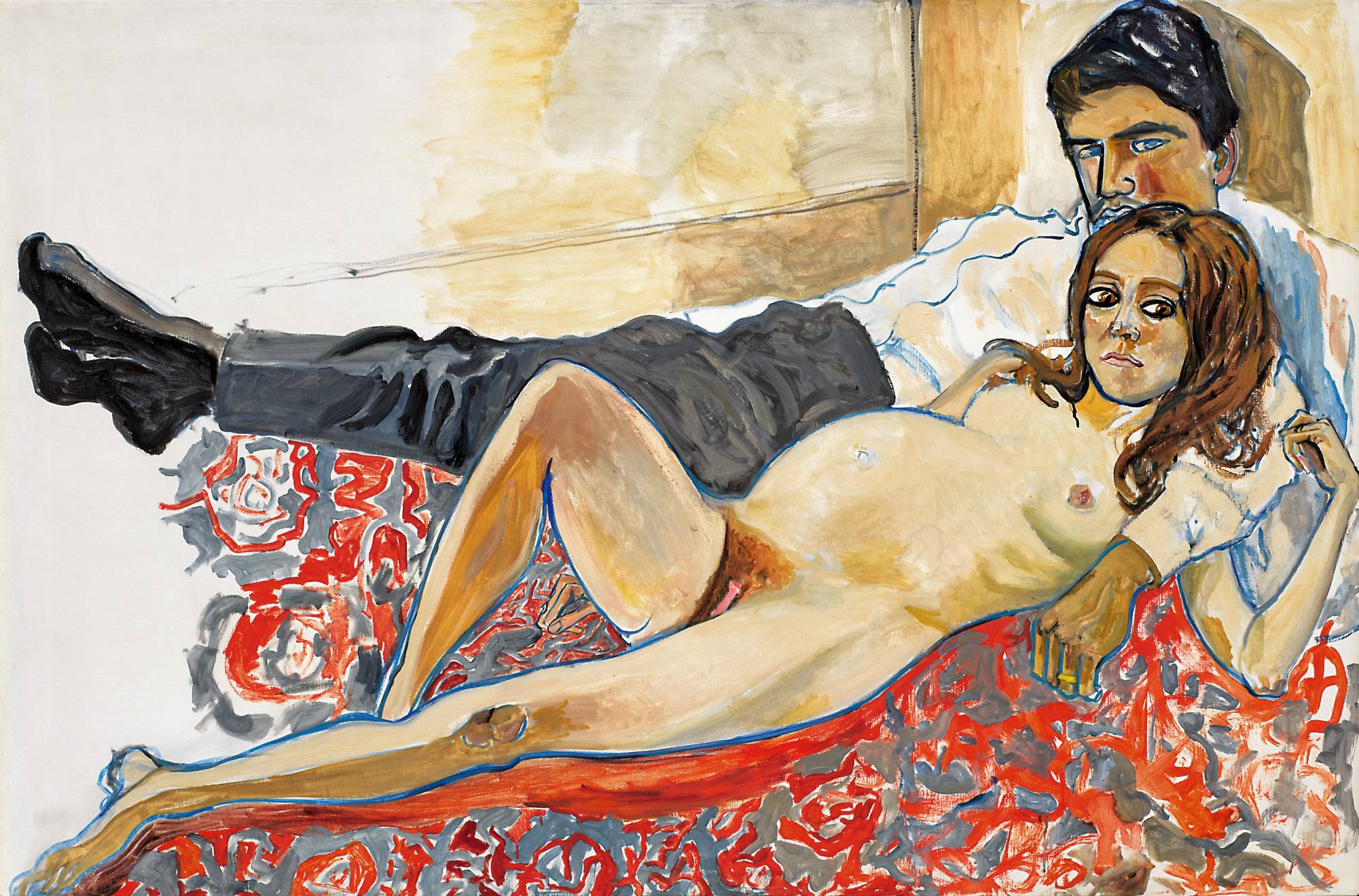

Most of the paintings in ‘Hot off the Griddle’ are portraits, though there is also a smattering of early interior and street scenes, as well as three accompanying films, of which Helen Levitt’s remarkable silent documentary In the Street (1948), depicting East Harlem in all its glimmering spit-and-sawdust, is a highlight. Nairne’s story-led solo exhibitions of New York artists at the Barbican – including Basquiat (2017) and Lee Krasner (2019) – tend to stage their early phases of tutelage and sacrifice in the eight small, dark rooms on the gallery’s upper floor, before leading the viewer downstairs into an expansive, light-flooded space of critical success. Nairne’s treatment of Neel conforms to this pattern; the upper gallery guides us through Neel’s early period of painting the poor on the streets of gilded-age Havana, Greenwich Village’s fabled inter-war bohemia and finally Spanish Harlem, where she set out to convey ‘the rich deep vein of human feeling buried under the fire engines.’ On display in the lower gallery are many of the works that made her name, including Marxist Girl (1972), in which a slouching Irene Peslikis, founder of the feminist NoHo Gallery in Manhattan, fixes the viewer with a confrontational stare. Also on show are several works depicting heavily pregnant women, including Margaret Evans Pregnant (1978) and Pregnant Julie and Algis (1967), in which an attractive young couple, she naked, he fully clothed, recline like dope-smoking odalisques on a wildly patterned bed.

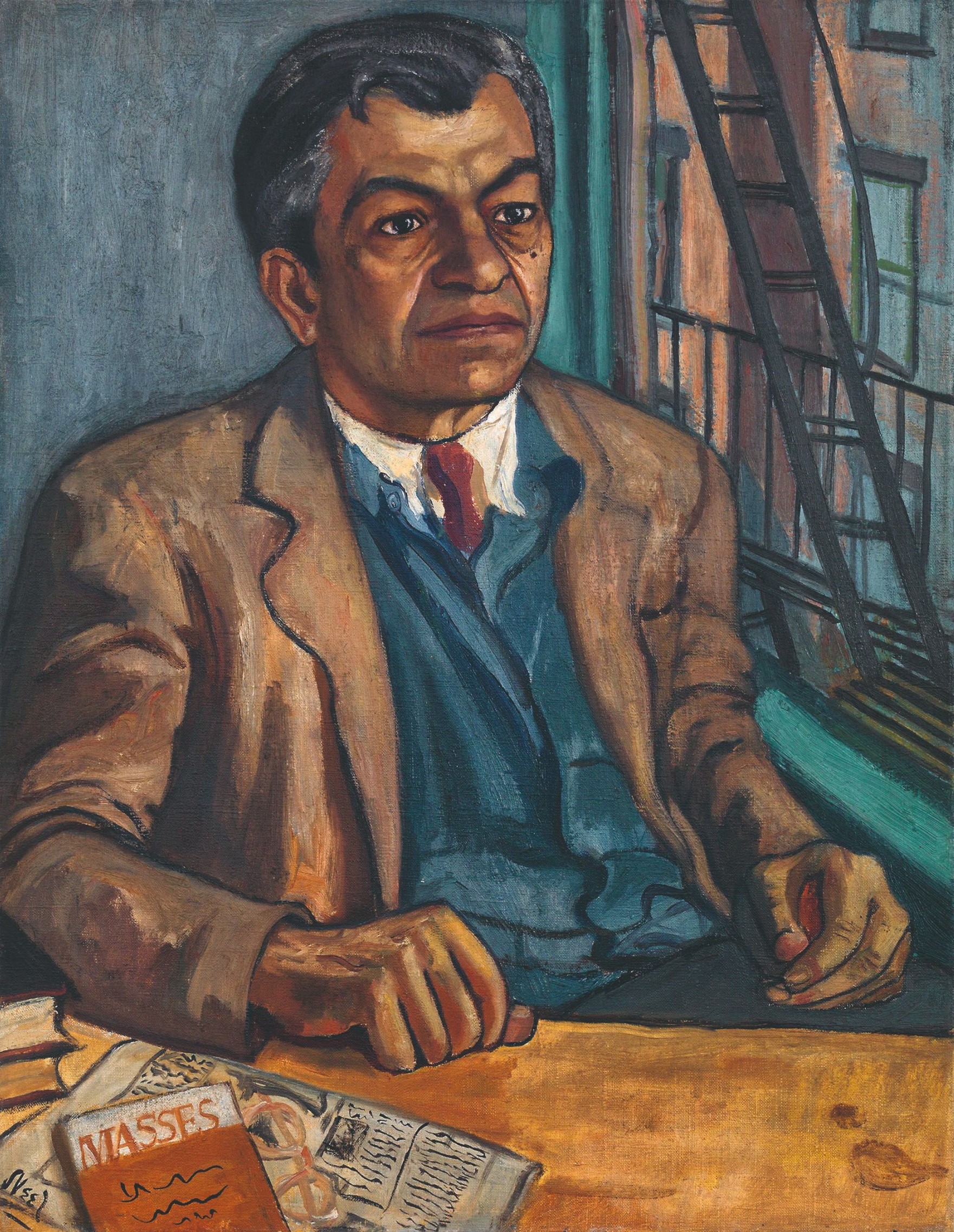

By the time Neel moved to the Village in 1932, she was already volunteering with the Artists’ Union, producing illustrations for their pamphlet Art Journal. It was through this work that she met Communist intellectuals, writers and activists such as Bonosky, Horace Clayton, Art Shields, and Mike Gold, whose portraits hang in the two-room ‘Anarchic Humanism’ section of the exhibition. The portrait of Bonosky (painted in 1948), a sometime Moscow cultural correspondent for The Daily World, is particularly arresting: eyes fixed on us, his beloved Tolstoy’s War and Peace on a makeshift bookshelf behind. In the 2007 documentary about Neel made by her grandson, Bonosky appears as an avuncular figure and a compelling commentator on Neel’s work and its politics. Shields was once recognized as the greatest labour reporter in the United States, while Black Metropolis by Clayton wasrecently reappraised asa landmark study of race and urban life in Chicago, yet these men are largely forgotten figures today. Neel’s preternaturally vivid portraits of them seem to insist on their place in history.

Gold, the ageing firebrand, poses in a red tie and white shirt, staring prophetically into the middle distance. His right fist rests next to a newspaper, his folded glasses and an original copy of Masses, the American socialist magazine that was dissolved in 1917, and which Gold relaunched as New Masses in 1926. In compositional terms, Mike Gold (1952) recalls Neel’s 1935 portrait of Pat Whalen, a longshoreman who helped organize a Communist-led insurgency against the corrupt leadership of the International Longshoreman’s Association. Neel did several paintings of Whalen, including one in which he is depicted tearing down a swastika flag from the SS Bremen, which she later painted over. Made with oil, ink and newspaper on canvas, Pat Whalen portrays, in Neel’s words, ‘the ordinary Irishman’ who was ‘absolutely convinced of communism’ Like Gold’s, Whalen’s blue-bloodshot eyes are fixed in the area over the painter’s shoulder, while his fists – which would smash bar mirrors in the port of Baltimore to intimidate landlords into serving black patrons – are pressed firmly, like a fervent preacher gripping his scripture, on a copy of The Daily Worker, whose front page announces a further wave of trade union uprisings in the steel and coal industries. Pat Whalen is the one notable omission from Neel’s Great Depression works in the exhibition. The concentration of American socialist portraiture in the ‘Anarchic Humanism’ rooms cannot but bring to mind a comment of John Berger’s: ‘If an artist is painting a chair, then she or he does not automatically make it a Socialist painting by placing a copy of The Daily Worker upon it.’ The conspicuous paraphernalia in these portraits – the left newspapers, magazines and books advertising both the subject and artist’s political allegiances – gesture to the constraints of a realism that must ‘tell’, not show, the viewer what it wants to say.

Neel’s devotion to portraiture – and faith in its political possibilities – not only put her at odds with Abstract Expressionism, but with dominant left-wing attitudes to art. Portraiture was widely seen as bourgeois, concerned with aristocratic deference, and, by mid-century, inferior to documentary photography. During the Federal Art Project period (1935-1943), which funded artists including Neel, the mural was more popular than the easel painting because it lent itself to narrative and public use (as decoration for infrastructure, for example). Neel, though, saw her portraits as displaying the dignity and humanity of those living under a system that degraded individuals in the name of individualism. When, in the 1930s, Philip Rahv criticized her for painting portraits, Neel retorted: ‘Well, one plus one plus one is a crowd.’ Like microhistorians who aim to understand an entire era by chronicling the life of a single person or community, Neel sought to evoke her subjects’ material world by studying how they sat within it.

The tension at work in Neel’s committed portraiture – between making paintings with political force and painting people as they are – is one that her best works reconcile, or rather don’t accept in the first place. As she moved from dramatic street scenes to quieter portraits of individuals, lovers and unconventional families in the second half of her career, Neel increasingly honed a kind of authentically political portraiture, matter-of-fact yet sympathetic, that refused the distinction between evoking social conditions – in her words, those of ‘the loser’ and ‘the underdog’ – and capturing her subjects accurately and vividly. Neel’s approach recalls Vivian Gornick’s statement on her parents’ Communist friends: ‘paradoxically, the more each one identified himself or herself with the working-class movement, the more each one came individually alive.’ Neel’s work undercut the belief, widespread among twentieth-century American artists and art critics, that realism was obsolete, with little chance of renewal in the name of either aesthetic or political progress. Through her frankly perceptive and defiantly démodé portraits, Neel showed realism to be a living method for indelibly representing ordinary people in a changing world. A radical vision ‘can be best transformed into living art by utilizing the living tradition of painting’, wrote Neel as a co-signatory to the ‘New York Group’ manifesto in 1937. ‘There must be no talking down to people; we number ourselves among them.’

Read on: Saul Nelson, ‘Opposed Realities’, NLR 137.